rogerpalmer.info

Photographs | Installations | Video | Books & Catalogues | Exhibitions | Texts | Contact | Links

Text:

| 'Repetitiveness without identicalness'. |

||||||||||||||||||

| By Ian Hunt Cell, 2000 |

||||||||||||||||||

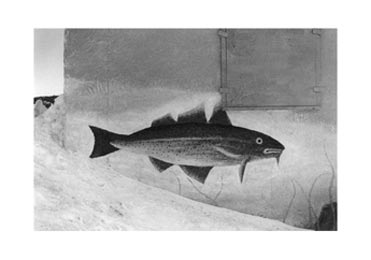

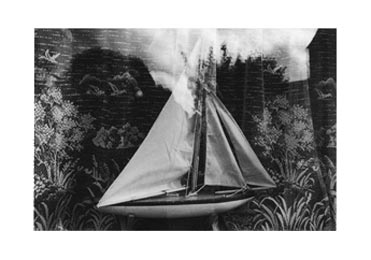

Roger Palmer's works divide principally into wall drawings and photographs. His engagement with photography is an intense one, which it would be possible to look at in several ways. But it should not be forgotten, when looking at this selection of recent works, that we are looking at half of something. The subject of Palmer's wall drawings will be returned to, as an understanding of their place in his practice and of some of the aesthetic features of the decision to work directly on a wall are directly relevant to the surfaces and the perspectives of the recent photographs. But first some ways through the photographic works need to be indicated, and something of their history. First it could be pointed out that having worked hard to establish a thematics of black and white arising from the observed world, from a particular engagement with their excessive meanings in South Africa, this thematics has been allowed to diminish - black and white still appear, but they are no longer so strongly coded. They always were pitched at a point 'between significance and insignificance'. They draw attention to themselves but often fail to communicate as messages, as in the magnificent white painted railway signs shown in Chain of Signs (1991). These convey something to a railway driver but nothing to the viewer other than what they are, and what they are is complex. A code without a contents(1) . This development of what might be called 'decreased vigilance' to black and white is related to another issue - that the photographs have arisen in recent years in a wider range of countries. Included in this selection are works made in Scotland, where Roger Palmer lives, South Africa, where he returns, Lesotho, which is a long way from Cape Town, Ireland, Canada, Uganda, and Greece. A particular tension was in place in Palmer's work in that he dramatised his encounter with South Africa, and gave it visual form. It is not enough to plot the biographical journeying with family, before and after 1990, without seeing that the works organised it. First a tendency to view things from some distance, as in the Precious Metals series; and then often as the presentation of near and far in equal divisions, as in the powerful series of vertical photographs of crumbling walls in a desertified landscape, made in 1989; and only then to a getting close to things; a getting close which then often comes to inhibit the longer prospect. The studies of signs, graffiti or painted images and words in the landscape, which Palmer has subsequently taken with him as a preoccupation to other countries, seems to have begun in South Africa, or if not to have begun there to have found some of their most telling outcomes as works. The use of reflective surfaces as a way of generating new types of pictures examining the dynamic of near and far, on the other hand, appears to have has arisen more recently in his work in Scotland. And it has been taken out from there to destinations including Nieu Bethesda and - unable to resist the allure of such yoked names - Aberdeen, which in this instance is not the stone town of Scotland, although the greyness of the image is appropriate to it, but a small town in the Great Karoo region of South Africa. Here the word CELL was noticed and photographed, with the reflected perspective of an empty street: dirt road (we intuit the colour red), gable ends of large houses (signs of prosperity at some point) and what looks like it may be a cemetery wall with decorative railings, all reflected in what may be a storefront. Aberdeen uses that characteristic shallow perspective. The vanishing point may be found somewhere in the large area of white unexposed paper within which each print is isolated, but it never figures within the image. When the subject is a reflective surface this angle of view can be explained pragmatically, by the need to exclude the reflection of the man with the camera - we don't, after all, succumb to the illusion that the photographs take themselves. But the shallow perspective appears in other works too, and has an insistence in recent works. Square-on pictures are still made, but it could be said of Palmer' s work that it no longer requires the square-on view in order to make clear its dialogue with painting and its artefactual quality, its evident constructedness. The shallow perspective also means that even when urban settings are shown, we rarely get a sense of how the street plan works, or a sense that we can easily orientate ourselves in relation to what we see. That sense of what remains beyond comprehension, spatially and culturally, is crucial to Palmer's work. Related to the works using reflections but distinct from them are the views through damaged, scratched or marked surfaces of perspex or glass, usually that of bus shelters, as in Loch Fyne, where the surface is dotted with stickers of football players which have themselves been drawn over by felt tip pen. These damaged transparent surfaces more easily allow a square-on view, and seem mostly to have arisen in photographs made on journeys in Scotland and Ireland, usually in places near open water. This part-biographical, part-aesthetic account of where and when visual tendencies emerged in Palmer's work is by no means complete. It could also be pointed out that in recent years the tendency to make works that consist of groups of photographs or which use serial imagery with insistence - and Palmer has made some major works using these approaches which are significant ones for twentieth-century art - has become less noticeable. The tendency has been to make individual photographs, as are all those reproduced here: acts of seeking for something, reflected back and forward into other works and other places. But at this point, having gained at least some sense of what makes Palmers photographic work so compelling and so generative of meaning, the wall drawings need to be considered, and something of their aesthetic history too. The art historical retrospect needs to extend to the advanced art of the Quattrocento in Italy, where it was in fresco painting within architectural settings that the mathematics and the aesthetic possibilities of perspective were first properly explored; and even to the 1960s and 1970s, when the wall drawing was reintroduced by conceptual artists such as Jan Dibbets, Sol LeWitt and David Tremlett, with varying emphases. In between these two points, and also relevant to Palmer's works, are the development of optics and perspective in the Dutch republic of the seventeenth century by artists such as Fabritius, Saenredam, de Hoogh, van Ruisdael and Vermeer. The wall drawings by Roger Palmer I want to focus on are those from found motifs or from words (words and images whose characters are slightly altered in the process of photocopying and projection from a transparency), which are then drawn on the wall using the point of a pencil. These motifs have included the ship Bengal Merchant, which departed from Port Glasgow for New Zealand in 1839 carrying the first settlers from Scotland. This drawing, measuring nearly four metres in length, can be found in the public library at Port Glasgow. Other drawings have been made from petroglyphs of animals, taken from a book on southern African rock art. When making these drawings, first the wall is carefully prepared and felt with the flat of the hand for defects. Then a transparency is projected onto the surface. The drawing is made with the silvery point of a hard 2H pencil. The areas of tone are not cross-hatched methodically, but produced by a line that circles on itself, feels its way into the contours of the motif. Palmer shows a respect for the surface of the wall that could be left as that - or interpreted more fully as a reticent but distinct love of surface. The word is not too strong. When making a work from a rock art motif in a gallery in Hartford Connecticut, An Orange Free State rock painting of four eland surrounded by zigzags . Palmer discovered in the process of drawing the curved scoring of a line from a work by Sol LeWitt that had at one time been made on the same wall. The finish of the wall was excellent, and the scored line had been repainted many times, but it was still enough to trip up the pencil. The discovery delighted him: the seemingly perfect gallery wall carried the shallowest archaeological traces of a work executed to the instructions of an admired artist, and was found when remaking a rock art motif - which would originally have been made and remade by different people on the same favoured and hallowed surfaces, over a long period of time. Palmer's drawings show that concern for surface, for facture in the patient but not entirely routinised labour that they require. (Facture, it should be noted, is by no means transcended or deleted in the work of LeWitt: the work may be drawn up by assistants, but they cannot do it wrongly, LeWitt has said, and the way each does it is particular). The classicizing aspect of LeWitt's art is a complex issue - in part it concerns his acceptance of illusory space - but one other point can be made here: that when making a serial work, the classical solution of selecting rather than presenting all possible permutations is frequently adopted(2) . Perhaps more importantly however, Palmer's wall drawings exemplify what Adrian Stokes, the English interpreter of Renaissance art, called a love of perspective, a love of space(3). The word is not too strong. In the shallow relief sculpture of the Quattrocento by, for example, Agostino di Duccio, or in the medals, frescoes and drawings by Pisanello, the hesitancy of early perspective has a particular beauty. In Pisanello can be found a post-medieval sense of a space in which animals wild and domesticated, flowers, trees and humans are in harmony, are portrayed as involved with each other culturally and spatially. The great patrons of the period such as Sigismondo Malatesta were of course bloodthirsty brutes. But Pisanello's work still has an unusual power to delight, and is mentioned here because animal motifs are significant in Palmer's work as a whole and he photographs depictions of them frequently. I suspect what he likes is the way they convey how foreign a place is to us, which is shown by what in that place is a familiar enough animal to be granted an image on the side of a building or as part of a civic crest. In this selection we have only three nicely painted chickens (Maseru), and the waterfowl flying across the pastoral lace curtain to be found in a window (Lough Swilly), against which the model yacht is drifting. This is a design that somewhere harks back to that vision of harmony between all living things, which survives most readily in fabric designs. Elsewhere Palmer has depicted or used the names of innumerable species of antelope, sheep, polar bears, moose, salmon (which are part of the coat-of-arms of Glasgow) and vehicles - trains, cars - which as Broodthaers once made clear in a print called Animaux de la ferme, are analogous to domestic beasts. Fortunately for the subject still under consideration, which is the love of surface and perspective, Palmer has also photographed in Lark Harbour what I take to be a herring. This part-snowbound, uneven wall in Newfoundland shows a fish painted with great care and charm, swimming in profile over indications of weed and rock. The leading dorsal fin touches the corner of a covered window. Although the wall is photographed square-on, the line of snow rising to the left can be mistaken for a receding line of shallow perspective. The plane surface of the painted wall is thus contradicted by another possible illusion.

A wall drawing has long been planned, though not yet executed, using an image from a small commercial boxwood engraving of the Forth Bridge, Scotland. The motif is to be projected at an angle to the wall; this would produce a drawing that can be read 'square on' only from the same angle. A precedent for this work is Jan Dibbets' Perspective Correction works, in which simple geometrical figures were drawn on the wall in his studio in 1969. There are other precedents, of course, in the optical play of Holbein and later in Dutch art of the seventeenth century, as already mentioned, which through inventive use of perspective and the camera obscura made paintings that still have a vivid thread of connection to the optical images of the world remade by photography. Many of Palmer's photographs reproduced here exploit shallow perspective with no vanishing point visible, as though they aspire to flatness but remain involved in the geometries of positioning that come with a Dutch rather than an Italian perspective. (Incidentally, it is hard to imagine Palmer making works in Italy, though he has made one in Greece. He has a particular interest in the anomalies and the conflictual aspects of 'new' countries, which include, stretching the term, Scotland and Ireland. Pictures taken in England, where he comes from, have become noticeable by their absence.) By referring to these two art historical moments - the warmth of the natural and human worlds portrayed in the art and space of the early Renaissance, and the slightly chillier factual world revealed to sight in seventeenth-century Holland - 1 want to argue two things. That Palmer's approach in his wall drawings and his photographs recalls the love of surface and the love of space of the early Renaissance, a sensibility which recurs in vernacular work like the wall painting of the herring, but that it is finally the slightly chillier and later, disenchanted illusions of space that determine the visual complexities of his recent works. However, Palmer's fidelity to black and white, to the monochrome re-enchantment of the world, can be seen as a promissory note for colour and warmth, not an abandonment or deletion of it. In relation to these works using reflections, it is not inappropriate to refer to a line from a seventeenth-century religious poem by George Herbert, familiar as an English hymn: 'A man that looks on glass, on it may stay his eye/Or, if he pleaseth, through it pass and then the heaven espy.' This is precisely the effect of Kerrera Sound (minus the bit about heaven). Kerrera Sound is a seemingly impregnable set of superimposed illusions. Looking through glass into an empty office or clubhouse adjacent to water - a built up shoreline of another side of the sound can be seen through the windows - one follows also the view reflected in the glass which can be seen darkly against the unlit interior. The horizon line in the reflection, hills with a light fall of snow, matches the horizon line seen through the window perfectly. But the two are incommensurate. The boat reflected on the left fits so perfectly with the view seen through the window that it is hard to locate it mentally as a reflection of something behind the camera.

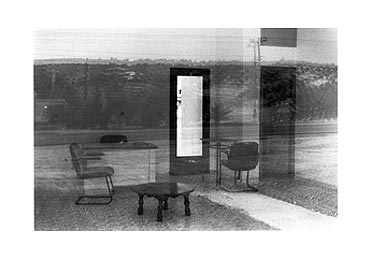

The twin of Kerrera Sound (1998) is Nikiti (1999), where a foyer or sparsely furnished office - cantilevered chairs, coffee table - appears as though immersed in what the plate glass in front of it reflects. The reflection is doubled by the thick glass, rendering the reflected view of road and built-up hillside less precise. The reflected image is a kind of homage to camera shake that seemingly affects only one layer of the image; it certainly suggests movement overlaying the cool stillness of the interior. At the centre of the photograph is a glass door through to a real, sunlit world, where bright sunlight, quite unlike the dark light seen in the reflection, falls on white buildings. It is an image of social life at some kind of standstill or removal. The view is close enough to perpendicular to the window for it to be mysterious that the photographer is not reflected. (If he was, of course, the image would not remain open to the viewer in the way it does.) Not for the last time viewers before Palmer's framed and glazed photographs find themselves standing at a distance from the work that seems to have been designed by the work itself, to be standing in a seemingly circular visual argument that does not exclude viewers but rather leaves them in a creative sense of uncertainty about space. Uncertainties before reflected surfaces - the ill-fitting mirror in an old dark frame erected as an aid to motorists on a loch shore road in a matchless image, Gare Loch, and the 'dark light' splashed with white paint that is found reflecting the dirt road at Nieu Bethesda - are social as strongly as they are spatial. Formally, the generative historical work in this tradition of visual uncertainty is Manet's Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère, with its mirrored reflection of the waitress and also the viewer - wearing an unfamiliar costume of top hat and moustache - in the wrong place.

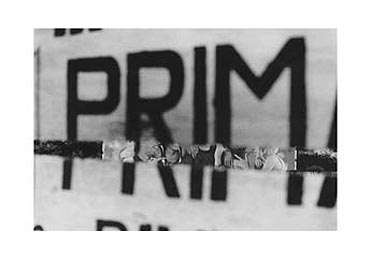

Having drawn attention to the quiet love of surface that animates Palmer's wall drawings, and some of the spatial qualities of his photographs, it remains to point out the prominence in these photographs of surfaces that are abraded, worn down, damaged and imperfect. The damaged surfaces are, in some works, ideological ones. In Namirembi, through a horizontal split in a sign showing, out of focus, the hand-painted letters ' PRIM -' (for a primary school) can be seen in precise focus an advertising hoarding: a glimpse of sleeked bodies in a carefree spirit appropriate to selling enjoyment, a soft drink or the knowledge - to those without the means to buy an education - of the wealth and forgetfulness they are to aspire to, visual anomalies familiar in the underdeveloped world, and not irrelevant to the experience of the overdeveloped one. Palmer tends more often to hint at social facts via neglected material facts. But in its bringing together of two surfaces, two depths, into the formal rectangle of the photographic print, Namirembi is quite consistent with the aesthetic meanings established and generated by his recent photographs, which have now reached an astonishing level of refinement and also of internal difficulty. To look at these works is to become involved in thinking how hard it has become for Palmer to make or 'find' them as precisely as he does. I imagine the emulsion of the film in his camera as though scored with favoured compositional lines, carrying its strong visual preoccupations out into the contours of a world that is not mastered by these preoccupations but revealed - 'afresh', but also recalcitrant - by such strong visual transactions. lan Hunt writes on art and publishes the poetry imprint, Alfred David Editions. 1, See the works published in Roger Palmer, 'Remarks on Colour: Works from South Africa 1985 - 1995', essay by Stephen Bann. Llandudno: Oriel Mostyn. 1995.

|