rogerpalmer.info

Photographs | Installations | Video | Books & Catalogues | Exhibitions | Texts | Contact | Links

Text:

THE RETURN TO INTERNATIONAL WATERS by Nikos Papastergiadis |

If painting is the privileged object of art history, and given that contemporary art practice includes a diversity of other media and new practices, then how well suited are the techniques devised within the discipline of art history for interpreting the meaning of art? In the current field, where artists are engaged in post-studio practice, making work which is a response to, or an engagement with specific materials found in particular places, the work that art is doing needs to be understood within new frameworks. The references to place and the relationship to the studio are rarely inalienable. Despite the numerous examples from Giotto to Rothko, who made paintings specifically to be displayed in particular buildings, the life of modern paintings is rarely confined to an exclusive venue. The intention of the artist to see his work outside of the studio may be marked by ambivalence, but it is also central to its conception. One of the tasks of the art historian who is interested in the social context of art is to follow this journey from conception to the places of display; the other is to read the content of the painting. Much of the sociological meaning of art has been explained in the form of an historical narrative. The social history of art has thus emphasised the temporal element of art. When the artist is not making art in a studio but on a specific site, and when this work has no substantial presence beyond this location, then this places conventional art historians in a difficult position. They cannot wait to receive the work in an alienable form. They must either go onto the site or forever miss the experience of the art. There is no belated response, for the only time in which the art exists is the time in which it is made and displayed within a specific place. To understand the meaning of this art, historians and critics need to recognise the significance of spatial elements. The art historian is now compelled to track not just the history, but also the geography of the artwork.

It is from this perspective that I begin writing about Roger Palmer's installation at the former offices of the Union-Castle shipping company in Southampton. It is also worth noting a question put to Palmer at the opening of his exhibition by a journalist: "Is there any of your work in this exhibition?" Palmer replied: "The exhibition is my work". The confusion between the exhibiting of the artist's own work, and the exhibition as the work of the artist, underlined serious conceptual issues over what are the boundaries, between the aesthetic and everyday objects, in an exhibition which utilizes found material and is located outside of sanctioned museum spaces. The first point to stress is that the city and the building were not fortuitously chosen. In the guide to the exhibition Oliver Sumner and Roger Palmer have outlined the history of the building in order to provide not just the background but also to establish its conceptual links to the exhibition: Union-Castle House was built in 1847 on the site of the Gloucester Baths, a Georgian building which stood on a tree-lined promenade, known as the Platform. Originally the port customs house, Union-Castle House was established in 1902, soon after the 1900 merger of the Union and Castle shipping lines. Union-Castle House is currently under conversion into luxury apartments as part of the regeneration of the Southampton Docklands. As the function of the building changes, so this temporary exhibition provides a bridge between different eras in its history. The location of the exhibition in this building, is thus not just a neutral issue of spatial accommodation but is part of a complex network of aesthetic and political decisions that have defined a project whose locations link South Africa and England. Given that it is now commonplace for contemporary artists to work on sites which are outside of conventional galleries and to create works which do not resemble studio-based paintings and sculptures, it is important to define the new relationship between artists and their work, as well as the broader questions of space and the everyday. At first glance the building can be seen as a frame which contains the artwork and enables viewers to focus their attention on the boundary between the aesthetic and non-aesthetic matter. In Palmer's exhibition this boundary is porous. Palmer deliberately chose the building because of its past history, but by also deciding to mount his exhibition during the period it was being 'redeveloped', he was both avoiding the pitfalls of romanticising the past, and opening an engagement with the changing architecture of the present. In contrast to other practices which require the viewer to scrutinise the sense of time and place that is staged in the work . Palmer's exhibition directs attention towards a sense of time and space that is both internal and external to the work itself. The loose boundary between the work in the exhibition and the history of the building does encourage a dialogue with the surrounding urban setting, but it also invites contemplation of past technologies for travel to distant horizons. The entrance to the Port of Southampton may have the modest greeting of 'Welcome to the Gateway of the World', but for Palmer the interest is specifically with the link that was forged with South Africa. The more general links that were forged by colonialism and facilitated by sea travel are also inflected through a personal history. Palmer was born in neighbouring Portsmouth and his partner in South Africa. The exhibition in Southampton serves as the double to an earlier show in Cape Town. In both there is the use of text and found objects. The textual links between the two exhibitions are not confined to the politics of post-colonialism, nor is there an over-riding code which predetermines the aesthetic value of the exhibited objects. Prevailing across these exhibitions, and even another paired exhibition between Scotland and New Zealand, is the fascination with the vessels of travel and the spaces between departure and arrival. The waters between nation-states, and the ships that traverse them, become metaphors for the process of transition and transformation. The Union-Castle Line had a near monopoly over the route between Southampton and Cape Town. It was a key player in the imperial links that have been cut and then left to rot at the edge of the dock. For over a decade the building was empty, but now, like almost every other port city in the world, this area has been targeted for 'regeneration'. Across the road from the Union-Castle building is the grand South Western Hotel building, formerly the Southampton Dock Railway Station, but now a complex of apartments with an active rail-line running through it which, once a month, services the Orient Express. Next door is Wilts & Dorset Bank now occupied by Jeeves of Hampshire Valet Service, and in the former Pilgrim House - a memorial to the departure of the pilgrims to America from Southampton - is Burns International Security Services. Beneath the fifteenth century Godshouse Gate and behind the French chapel of St Julien there is a reminder of the Genoese presence in the commercial centre of the city. Even the Lord Mayor was a foreigner! These old cities decline and recover. Strangers come from different directions bearing new duties and stigmata. Today traders are not so visible as asylum seekers. Corporate arrivals are now providing the catalysts for 'regeneration' by occupying buildings which have been left empty, oblivious of the history of the past industries which slowly rust or hide under new coats of paint. The city now waits to be filled, but the fit is never even. Gaps remain. Between the fragments of medieval walls, between meals in the mock Tudor pubs, between the pavements and the entrances of the Victorian hotels with their gardens paved for the convenience of cars, and along the broad one-way streets that lead to the dock, there is the constant reminder of the conflicting ambitions that seek to claim a space in the city's identity. Palmer's exhibition is a space in which the history of a city can be re-considered, not by celebrating a particular moment in the past or making triumphal claims about the present, but in casting our gaze toward the horizons of other journeys. These horizons are initially announced in the long list of names of the Union-Castle ships that left from Southampton. Unlike the bitter-sweet melancholy of Alan Sekula's photo-narrative Fish Story, which documents the impact of containerization on global shipping throughout the 1990s, or Damien Hirst's decision to stage Freeze, the 1988 Degree Show of his Goldsmiths College contemporaries, in a former seaman's gym in London's docklands, Roger Palmer's work is neither attempting to represent a disappearing history, nor grabbing a derelict space in order to aestheticize the contradictions between art and industry. Palmer has chosen to work in a space during the process of its 'regeneration' by property developers. While most artists would prefer to work with a building in a state of ruin, Palmer accepts the work of the developer as part of the context with which his art must work. The old building can in many ways withstand the contrary ambitions of both the artist and the developer, and the significance of the occasion does not rest on competing claims over which is the most sympathetic to its original design. Palmer harbours little nostalgia for the specific history of the Union-Castle shipping company. There is also a stoic countenance that meets the asymmetrical partitions of space and the circumcision of columns, or the tardy references to the past with a mahogany frame to echo a captain's office, and an inlaid compass that points in the wrong direction. Rather, the relics from the company's history, and the remains of the building have been incorporated into a metaphorical exploration of the way a sense of home is transported.

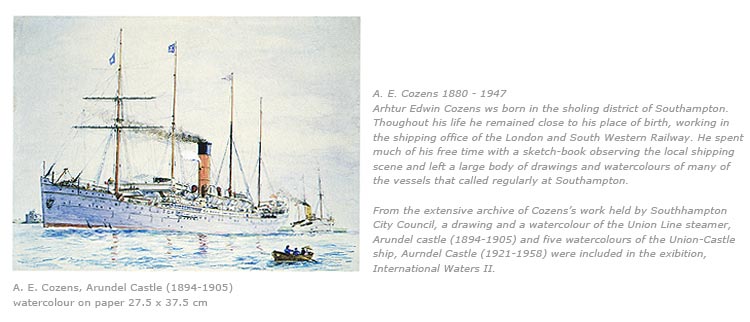

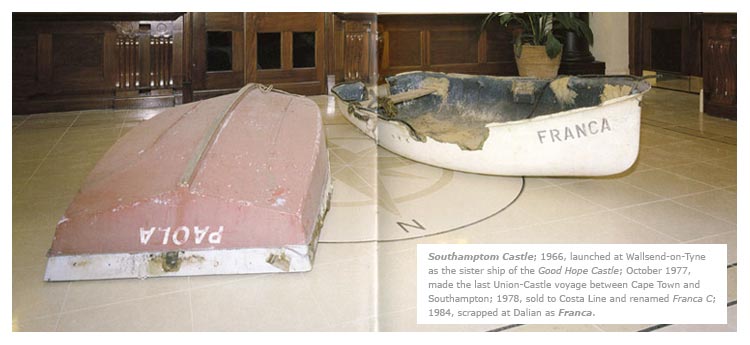

Palmer's use of materials in this exhibition continues with the fundamental principles of conceptual art. One of the objects of conceptual art was to break away from the institutionalised hierarchy of media and choice of material for the production of art. By rejecting the ideology which defined the superiority of painting in terms of visual autonomy, conceptual art also attempted to transform the relationship between art and the everyday by expanding the range of materials that could signify as artwork. The objects in this exhibition are almost banal, like the use of an old receipt book, the only object that Palmer salvaged from the building during its derelict phase, or even the distinctly amateur watercolour drawings by A. E. Cozens, a former shipping traffic officer who spent much of his time sketching the local ships, which had been stored in the Southampton City Council Maritime Archive. The choice of materials in this exhibition is not governed by conventional aesthetic criteria, but by a desire to initiate a change in the way we think about the objects and consequences of travel. He has not in any way attempted to stage an exhaustive history. One visitor complained to Palmer that she had more artefacts stored in her attic than he had on display. Palmer was more concerned with how a few objects could trigger new messages once placed in a showroom flat, freshly fitted and painted but not yet occupied with furniture. These objects did create a haunting ambience. On the one hand they appear quite lonely, not crowded like they are normally in the rooms of heritage museums. On the other hand, the result of spreading the objects apart, made them appear like beacons issuing silent signals to viewers to consider the contours of a landscape that was being submerged beneath the new tides of urban development. The sense of time that is staged in this space is therefore disjunctive. Past and present intertwine like in a movie where the protagonist, perhaps it could be Peter Lorre, appears as a taxi driver and then narrates stories to his passengers about his early adventures as an able-seaman. A deep fatalism, beginning with the names of the last two Union-Castle ships, Southampton Castle and Good Hope Castle, runs through exhibition. Most of the earlier ships were named after British castles, proud claims about their impregnability. However, to end the line with a ship named after the bottom corner of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope, is a belated admission to the capriciousness of the elements which dominate the mythology of shipping, and an acknowledgement of the other pole in the colonial equation. The naming and mapping of colonial space, often unconsciously, expressed the desperation as well as the triumph of the coloniser. Paul Carter's seminal book, The Road to Botany Bay, which retells the story of colonial encounters from a spatial perspective, also focuses on the naming of bays and mountains as a way of gaining an insight into the limits of the explorer's inner world. To journey across the sea is always both metaphorically and meteorologically an encounter with the unknown. Since ancient times, sailors have tried, through prayer and offerings, to appease rather than conquer the sea. Their own destiny is always uncertain. Palmer echoes this anxiety through the juxtaposition of the 'biography' of the Good Hope Castle and the Southampton Castle which is stencilled around the cornice spaces of the foyer, and the positioning of two battered dinghies in the middle of this space. The text of this piece reads: Good Hope Castle; 1965 launched at Wallsend-upon-Tyne to provide a mail service between Cape Town and Southampton in less than 12 days; 1973 severely damaged by fire near Ascension Island; 1978 sold to Costa Line and re-named Paola C; 1984 scrapped at Shanghai as Paola. Southampton Castle; 1966 launched at Wallsend-upon-Tyne as the sister ship of the Good Hope Castle; October 1977 made the last Union-Castle voyage between Cape Town and Southampton; 1978 sold to Costa Line and re-named Franca C; 1984 scrapped at Dalian as Franca.

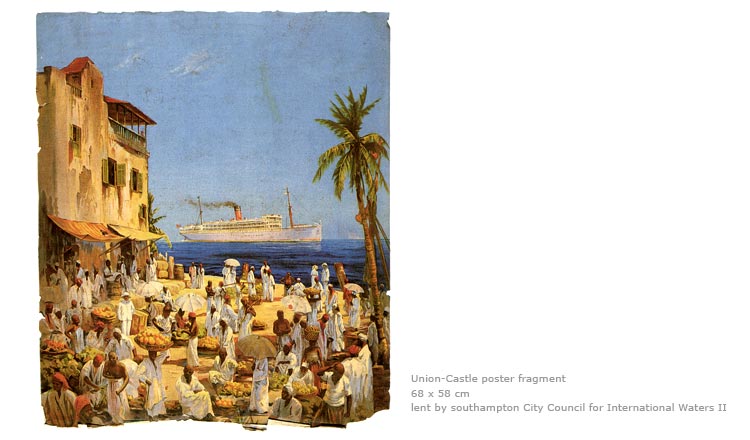

The two battered dinghies which lay in the foyer, made of flaking wood and worn out fibreglass, found in the scrap section of a sailing club, are also named Paola and Franca. The coincidence of naming may be staged but it also underlines the vulnerability of these mobile 'castles'. The dinghies in their decrepit state echo the decline of the industry and the demise of the colonial order which they served. They also signify the pathos within the colonial spirit of commerce and exploration which sought redemption through the ultimate adoption of feminine names for their vessels. There is a pained sense of justice in the knowledge that these ships often, in contrast to the pomp and ceremony of their launching, end as scrap in remote places like Gin Drinker's Bay, Kowloon. The geography that colonialism attempted to conquer eventually engulfs the very vessels of empire. According to Peter Newell, a historian of Union-Castle ships, the atmosphere on board the ships was stiflingly English. The evidence of an exclusive English palate - 'Corned Beef Cakes, Tomato Soup, Roast Potatoes' - is still visible on the original menu cards from which the model R.M.S. Pretoria Castle is constructed. Palmer has put this model on display. Apparently the decor was also classical Home Counties kitsch, with no evidence of influence from the cultures in which the ship docked. Through a vinyl wall-text, Palmer informs us that between 1910-1961 the 'Round Africa' mail steamship service also stopped at Gibraltar, Tangier, Palma de Majorca, Marseilles, Genoa, Naples, Tunis, Suez, Port Sudan, Aden, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Dar-es-Salaam, Beira, Lourenço Marques, Durban, East London and Port Elizabeth. The shimmering differences of each horizon, the palpable contrast of every market place, the cacophony of languages all seem to be arrested by the interior of the ship. Inside you could feel that you never left home. Palmer plays with these contradictions in subtle ways. He paints the Union and Castle flags onto the wall inside the main living area in a way that they could be mistaken for the Cross of St George or the Cross of St Andrew. The ships, through their flag and moving architecture, symbolically stretch the boundary of home as they travel between the mother country and the colonies.

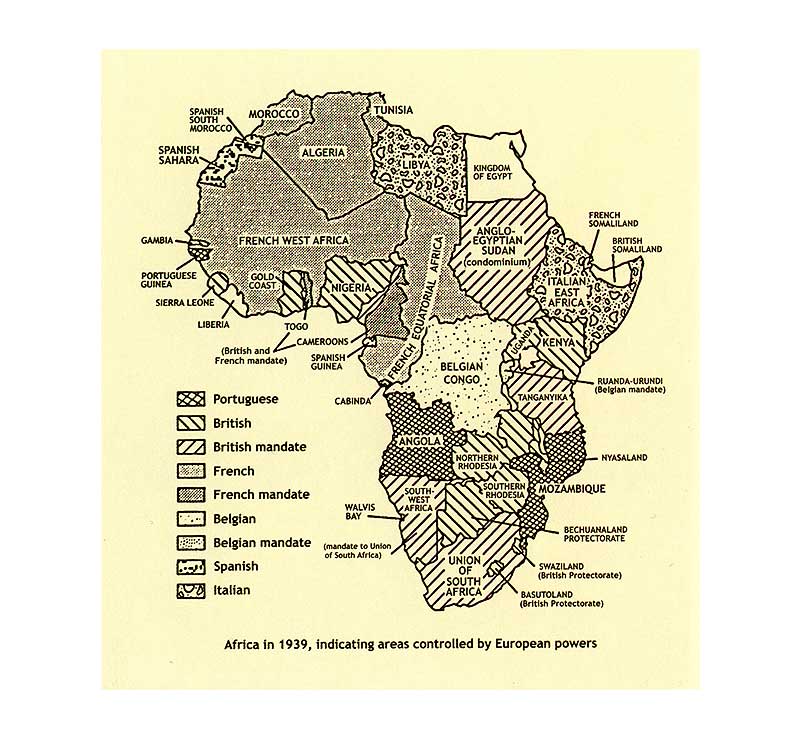

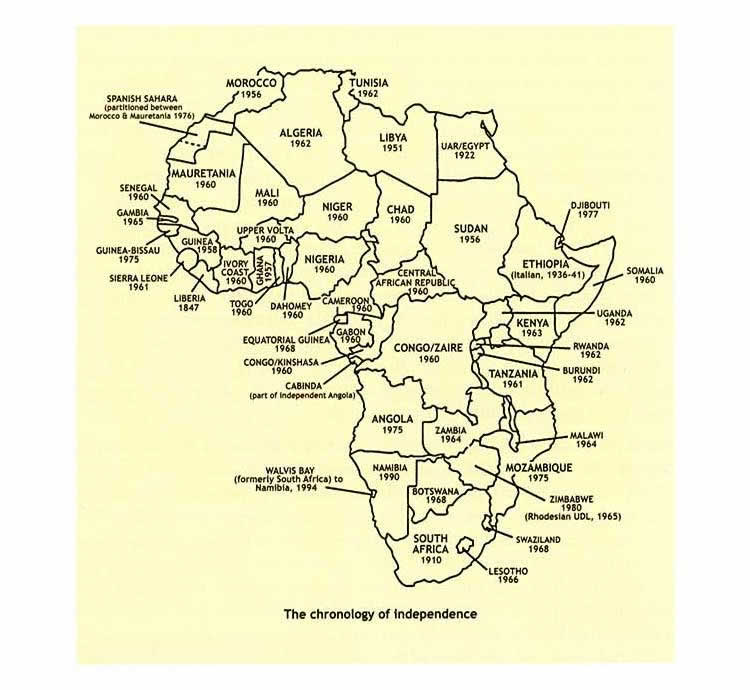

There is also a framed poster of an African market scene, which shows one of the Union-Castle ships arriving in the background. At first glance it appears that the ship and the colourful market are meant to stand as contrasts of two different worlds. Yet, in the midst of the market, there is one figure whose attention is not wrapped in his own labour but reciprocates the gaze of the viewer. A typical colonial agent, dressed in a white suit and a broad felt hat, stands in the imperious centre of this vibrant exchange. The sparseness with which Palmer has filled his rooms is there to contrast both teeming cultural flows through which those ships navigated and the cluttered nostalgia of their decor. Palmer further illustrates the symbolic connections between these distant places with this text which is displayed on the wall of the room in which the model of R.M.S. Pretoria Castle is placed: In 1947, the Pretoria Castle was launched by Mrs Issie Smuts, wife of Ian Smuts, the then Prime Minister of South Africa. As she refused to travel to Belfast for the ceremony, all the appropriate technology of the time had to be enlisted to ensure that 'Ouma' Smuts could nevertheless launch the largest liner yet built for the South African trade. And so it was arranged that she should press a button in the sitting room of her home in Irene, Transvaal, thereby triggering an electronic impulse that would be transmitted by landline to Cape Town, whence it would be sent by radio to London and there re-transmitted by landline to Belfast. There the impulse would release a bottle of South African wine to smash against the bow of the new liner and also set in motion the launching mechanism. Thus shortly after 14.25 on 19 August 1947, and preceded by the pidying of several Afrikaans folksongs, Mrs Smuts voice, relayed by radio from Soutli Africa, came clearly over the public address system at the shipyard: "I name this ship Pretoria Castle . May God protect the good ship Pretoria Castle and all who sail in her." Mrs Smuts then made the sam e pronouncement in Afrikaans and pressed the button. In 1966 the Pretoria Castle was acquired by the South African Marine Corporation (Safmarine). At a ceremony in Cape Town she was re-named S.A. Oranje by Mrs Betsy Verwoerd, wife of Hendrik Verwoerd, the then prime minister of South Africa. This text succinctly presents both the power of white authority in the colonial setting but hints at the possibility of succession. The reluctance of Mrs Smuts to travel for the launching of the ship is but a minor indicator of a brutal and introverted world. Perhaps more ominous is the use of the new telecommunications which not only relayed the message but also signalled imminent obsolescence of the ship even before it commenced its 'maiden' journey. Palmer teases out this double sense of connection and detachment, emergence and expiry, through the juxtaposition of a model of R.M.S. Pretoria Castle that was built from menu cards by a steward working on the ship. This quaint model and a single menu card dating from a later period when the same ship had been re-named S.A. Oranje, are both placed on plinths and encased in shields of Perspex plastic. By elevating and protecting these objects Palmer is not trying to make a claim over the status of these quasi-ethnographic objects, rather it is an ironic glance at the pretension of the aesthetic object in art and the blinkered vision of colonialism. The moral tone that is expressed against colonialism is tightly subdued, not due to Palmer being a naturally cautious person, but because his practice is to heighten the complex dramas of a complex system through its subtle revelations in the details of daily life. The smug miniaturism of the model ship and the starchy provincialism of the menu card could be read as damning comments on the cultural introversion that colonialism constituted as a social norm. Throughout the exhibition there is a constant attention to the way names change. The Pretoria Castle is sold and renamed S.A. Oranje, the Good Hope Castle becomes Paola. The explicit links between commerce and colonialism become less visible and are re-written in the era of independence. Palmer has also pasted maps showing the changing names of African countries during decolonization. We have become more aware of the growing gap between political freedom and the substantive gains in cultural recognition and economic prosperity. Names of ships take on the ambition of their masters, but also, when reduced to scrap in foreign ports or even renamed after a stranger's girlfriend, can reveal the pathos of their destiny. Palmer's exhibition, which has tried to register these shifts in vision in its subtle attention to name changes, is also about measuring the different kinds of claims for being in the world. The story of sea travel, the way it has changed in the past few decades, can be thus glimpsed by the confidence or hope, the origin or destiny, the personality or mythology of its nomenclature. The contrasting landscapes, of past and present, the colonies and the 'mother country' are never watertight. Space can never remain a blank stage upon which a single will can draft the narrative of action and response. Geography, like culture, thrives on difference. The ports must have been sirens in the ears of sailors, beckoning, dazzling, seducing. Kavadias, a Greek poet who knew these routes from his time as a ship's pilot, wrote a series of poems called 'The Southern Cross', in which he merged images that included memories of a knife bought in the market, the rows of barber shops behind the shipping offices, and the minotaur in Picasso's paintings. These memories are triggered by the handling of small objects. The image of the knife offers more symbolic than real protection. It can be kept close to the body as you travel, but it is also a trace of the jagged contact with multiple cultures. In Kavadias's poems the sense of place is entangled, combining the yearning for home with the desire for the other. Palmer has travelled many times between England and South Africa, perhaps from these travels there is the recognition of the possibility of having a home in both places, but more importantly there is a more abstract sense of openness that comes from recognising the spaces between these ports. Palmer is deeply aware that the age of the big ship is over for human migration. The only people who travel are paradoxically the privileged and the desperate. The rich cruise through the tropics and the poor try to land in the West by stealth and darkness. Human traffic is now mostly regulated by the air. While the numbers of people on the move is now greater than it has been at any other point in history, the image of the ship can stand for the ambivalence of leaving and for the time apart from home, a time in which the sentiments and expectations of being are more powerfully mixed with the dreams and hopes of becoming. End of text. Below: Maps illustrating the changing names of African countries during decolonialization.

|