|

|

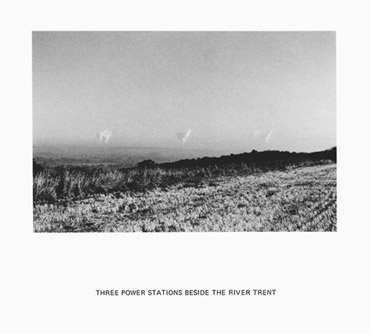

| Three Power Stations beside the River Trent, 1981 |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

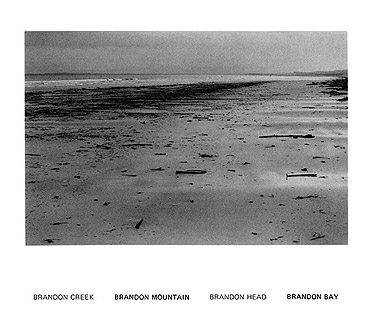

| Brandon Cree, Brandon Mountain Brandon Head Brandon Bay, 1981 |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

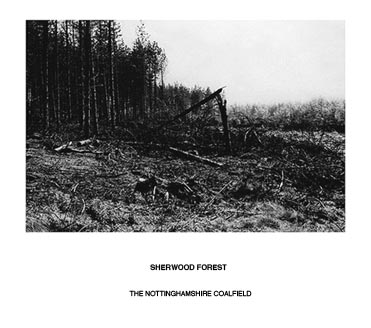

| Sherwood Forest, The Nottinghamshire Coalfield, 1979 |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

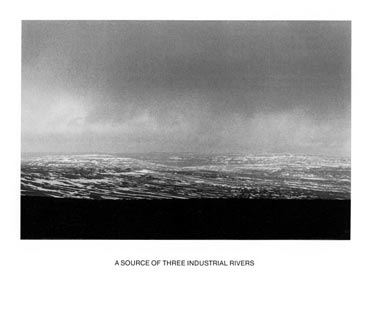

| A Source of Three Industrial Rivers, 1978 |

|

| |

|

|

ROGER PALMER photographs in high, wild and handsome terrain - in the Midlands and further North. He is easily taken to be a romantic photo-artist, in solitary communion with an often sublime Nature, forested or frosted. On the other hand his photographs are as interesting as they are romantic. Interesting in the sense that they make distinctions, and invite us to use our judgement - even as we are overawed or set at naught by spaces and skies which stretch beyond the farthest horison.

Three Power Stations beside the River Trent exemplifies this duality. The horizon is as remote as any horizon might be, seen from trodden paths, and the sky is an indifferent largeness, against which the power stations make scarcely any impression. Yet the impression they do make should not be taken for granted. From left to right plumes of steam detach themselves from the horizon and become, eventually, like clouds. We know that the blown mark to the right is man-made, not because it is intrinsically so but because the other elements in the set tell of their origins, being linked more pointedly to the ground. Whatever else is on show we know in the same way. This blackness we know to be a hedge because, nearer to hand, it resolves to show a tree in silhouette. That grey ground we know to be stubble because it is continuous with this flecked foreground.

Roger Palmer asks us to pay heed to what we see, and also suggests that we are conscious of more than we see. Three power stations. Yes, of course! But with that said or read, what then? Words resound to fill these large spaces, and would fill them completely but for such resistant matter as the plumes, stubble and fence posts which both make and break the sets of which these images are constituted. Meaning emerges from nothing in isolation, but from things in relation to each other and in relation to the words which describe them.

Long captions combine with wide images. The captions have place names, locations, measurements and/or rudimentary descriptions. The pictures generally show a continuous space, running from a particularised foreground to a generalised background. Yet each image is different, and not simply through change of location. Words sometimes sound against the photograph, bringing their own richness which finds no adequate response out there. Brandon Creek Brandon Mountain Brandon Head Brandon Bay exclaims against as level a strand as might be found anywhere. The place resists the name, and the name repeated makes a chant to match the place. By contrast the steady prose of Patches of Sunlight Moving across Frozen Hillsides makes a line as clearly disposed as that of the orderly hills. Sherwood Forest inscribed over The Nottinghamshire Coalfield mimics the place and its making: decaying woods subside into the earth, forest becomes coalfield, just as receding stands of timber turn from trees into forest. In A Source of Three Industrial Rivers the caption is at once indicative and suggestive; industry is nowhere to be seen and sensed, but what looks at first sight like a flowing passage of hall-thawed land falls away, as the caption says, in three directions. Representation and meaning are as elusive as the folds in this snow-streaked upland. This elusiveness becomes the subject of a set of recent pictures, not illustrated here, A Clearing in Wark Forest. The photographer moves in a narrow arc to one side of receding line of timber, a pile of stakes and a shed. From one neighbouring spot to another the site shows itself quite differently: differently enough to look like another place.

A Clearing in Wark Forest is one of several composite pieces taken and put together over the past year or so. The most successful of these, certainly the most complicated, is a four-part arrangement, A 1979 Barley Field, of a variously gouged and cultivated field-edge. In the three-part forest-set the principal elements make surprisingly different emphases as our viewpoint changes. In front of the barley field we are asked to note temperament as well as perception, for each piece makes a quite distinct and separate claim on our attention. Here the field is a site of action, a headland marked by turning circles and furrows. Taken from another viewpoint and at a slightly different time the field looks like an abstract composition strung beneath a severe horizon. In milder weather the site shows signs of change, of a turning moment between frost and thaw. A fourth time, a romantic cloudscape brings turbulence and reminders of distant force and scope. A practical observer becomes a geometer, before being returned to the thawing contingencies of landscape and eventually to inwardness suggested by piled clouds.

Above all Roger Palmer is a perspectivist, moved continually by the idea that whatever he sees is seen from a particular viewpoint and in relation to something else, to a word, caption or recent memory. Similarly he is moved by evidence that wide shores, mountains, fields and valleys are made up of particulars. At a certain point these ears of corn become a wheatfield, and these fields become a landscape. Random fragments of driftwood and weed on sand become a beach, and trees become a forest. This place, here and now and composed of specific items, shades into another place more abstract than particular - a place of universals, ground, horizon, sky.

Romanticism is only one of several elements in Roger Palmer's art. When it does appear it is bracketed, checked and opposed by this or thai plain detail, or put into a system where comparison and analysis become possible. There is nothing else in photography absolutely comparable. Richard Long and Hamish Fulton have, to a much greater degree, time and self as their subjects. They find pictorial equivalents for, or refer to, what befell themselves over that time in that place. Roger Palmer asserts himself less: places precede him, as do words and art's forms. He works in the public domain with commonplace raw material which slowly picks its way towards major universals of earth and sky. He includes just enough - a form and its meaning cogently folded over, with no distractions. In painting there is more which is comparable: Markus Lupertz with his trios of romantic and evocative subjects (thus shown to be designed rather than inspired); Jasper Johns making paintings out of number-sets and emblems, continually working around the point where the particular becomes general and vice versa. |