rogerpalmer.info

Photographs | Installations | Video | Books & Catalogues | Exhibitions | Texts | Contact | Links

Text:

Associations of Sensibility by Stephen Bann |

||

|

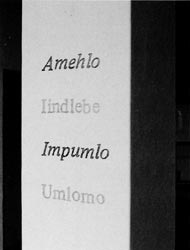

What is remarkable about the work of Roger Palmer is that it has developed as an extended allegory of the process from which it derives its material form. In the context of a retrospective exhibition, at any rate, the development over ten years calls out to be interpreted in this way. But this should not be confused with the relatively simple issue of formal development within a pre-established vocabulary of visual motifs. No one could be less formalist, in this sense, than Palmer. The point is that each move has generated the next through a controlled slippage of meaning: through the logic of displacement (or as the literary critic would say, metonymy) rather than through the accumulation of sense. This means that, at each juncture, the work remains astonishingly open, while at the same time it maintains its unity as a part of the greater whole which is presented to us in this show. Yet to argue that Palmer's work is an allegory of process implies that one should be able to specify from the start what process this might be. Obviously, on one level, it is the photographic process. The notable previous exhibition of his work which opened at the Serpentine Gallery in October 1986 bore the title 'Precious Metals'. From this one might infer that he has always been aware of the special kind of contract which binds the photographer to the visible world: namely that the chemical process which permits the faithful representation of infinitely varied substances and surfaces has itself traditionally been dependent on elements of the highest value, like silver, platinum and gold. It is through the indexical registration of light on these metals (in the form of washes and salts) that photography has been able to express the endless catalogue of objects and associations that make up the everyday world. Photography is always slumming, one might say. Or alternatively, photography is always performing a kind of aristocratic alchemy on the jumble of appearances. This point, however, risks aligning Palmer with a photographic tendency in which, distinguished through it may be, he has no particular stake. The great American photographers of the early part of the century were indeed highly skilled in developing an aesthetic of the superbly crafted print. For them, to be a photographer was a legitimate way of responding to the challenge of modernism by deciding to be that particular kind of artist. Yet in Palmer's case, the question of whether he should be seen as a photographer at all is one that needs to be asked. Certainly a good proportion of the work exhibited here does not fall under that heading. Nor does it really help matters to change tack and assert that he is a conceptual artist, even though conceptual art does indeed draw upon the same spectrum of media as he has grown accustomed to using. For 'conceptual artist', like 'photographer', is a designation that normalises particular processes, and particular ways of working, whilst Palmer's achievement has been to make us think afresh about these very categories, and their mutual boundary lines. If the word 'photographer' is, in the end, more helpful than not, it is because it refers us back to a stage in the development of visual representation when uncertainty about the potential uses of 'The Pencil of Nature' was a spur to a particular type of creativity. William Henry Fox Talbot, the inventor of the positive/negative process, has long been rescued from the stigma of being an innocent primitive, who pointed his camera in any direction that pleased him. The picture of him which has now emerged, in large measure because of the research of Mike Weaver, brings into relation his photographic work and his long-standing interest in etymology and ancient systems of writing. It may well be that Fox Talbot intended many of his photographs to be emblematic: that is to say, images which contained hermetic symbols deriving from the & and iconological traditions. At any rate, the simultaneous preoccupation of Fox Talbot with questions of language and questions of pictorial meaning is beyond dispute. This is not just a frivolous allusion to make in the presence of Roger Palmer's work. For if he has, so to speak, progressively deconstructed his own practice as a photographer, what remains is not just a series of detached components but, on the contrary, a kind of matrix for producing meaning which closely resembles the potential of photography in its earliest days. I think of Nicéphore Niepce's anxious attempts to bring together a trio of experts who would be able to exploit the new and exciting technique of capturing light rays on a chemically treated surface. For him, it was a question of supplementing his own skill with that of Daguerre, inventor of the diorama and thus far more knowledgeable about the use of the lens and the camera obscura. But it was also a question of involving a notable Parisian engraver, who would be able to advise on the production of high-quality prints. Photography was thus, for a time, spread-eagled between three different vocations: to compete with the fine-art print, to lend its power of illusion to the regime of spectacle, and to register its authenticity as a scientific effect. For Palmer, the spectrum of possibilities does not open up in precisely the same way. But it is noteworthy, at the same time, that he has opened up the conventions of exhibiting in a way which recalls this situation. He began by the fairly modest move, anticipated by other artists of his generation, of bringing photographic prints into association (the 'triptychs') and providing them with written captions which stimulated interpretation on several levels. He continued by opening up new spaces, both by investing his own domestic space with semi-private works belonging to the same system as the gallery exhibits, and by treating the gallery shows as full-scale installations. He also developed collaborations. Carol Fester has carried out embroidery word pieces for him, and a good proportion of his recent work invokes an association with the South African artist (now deceased) Chickenman Mkize. The present show thus bears the traces of a movement away from an idiom that would have placed him reasonably securely within the parameters of contemporary photographic investigation. But it is also a movement which re-enters the history of representation at precisely that time when photographic practice had not coalesced: when the photographer still roved a little uneasily on the fringes of the Academy, forming strategic alliances wherever it was possible. All the same, there is a kind of reserve about the position of the photographer artist, which Palmer's work expresses with great consistency. The fact that he paints paintings, and collaborates on craft-based work, does not mean that he implies no fundamental difference between the traditional media and the special vision which photography, right from its inception, tended to foster. In one of his letters to Niepce, dated 15 november 1829, Daguerre cautioned his colleague on placing too much reliance on the skill of the engraver, which would in his view detract from the effect of photographic representation, however skilful in its own terms. As he pointed out: 'Nature has its nativities, which one must be careful not to destroy'.(1) It is a warning that no one would think of addressing to Roger Palmer. On the contrary, everything has been done, over the full range of these works, to inhibit a precipitate judgement on the part of the spectator. The scales are tipped in favour of the world of things. ----------- I have before me two images from the series which culminated in the Precious Metals show of 1986. In both of them, the foreground is filled with a saloon car, lacking its wheels and indeed any signs of its previous utilitarian function: possibly a Ford Taunus, but in any event one of those cars which seems symbolic of the Western way of life in the era immediately following the Second World War. Viewed from the side, it virtually fills the horizontal format, set as it is against broad prospect of a desolate terrain relieved only by a few hardy patches of scrub. On the horizon, however, is another man-made artefact which, because of its position seems slightly ambiguous. According to a convention of viewing which originates with the rise of landscape art and the search for the Picturesque, this might be expected to be a castellated building falling into ruin. It crowns the composition, as we might say. But the propinquity of the featureless terrain, and the deserted car, make it overwhelmingly likely that this is a structure which has also been abandoned in the recent past: not an edifice of noble stone, but a deliquescent hump of low-cost materials, left to decay in ignominious solitude. There is, however, a crucial difference between these two images. First of all, the viewpoint of the camera is slightly to the fore in the initial photograph. We recognise, by comparison with the next that the barely perceptible line which blackens a section of the bottom edge is the upper end of a piece of scrap, probably serving from the abandoned car which complements the distant building through introducing a symmetry between top and bottom. Secondly, and even more evidently, the light conditions under which the two photographs have been taken are not the same. In the first, the side of the car facing us is in deep shadow, and the building, equally sharpened by the light, acquires a more engaging profile. In the second, the side reveals itself as white , or at least light in colour, whilst the distant structure displays the unrelieved monotony of its surfaces. Photographers from Fox Talbot to Ansel Adams and Bill Brandt have been ready to exploit the particular resonance which derives from the accentuation of contrasts of light and dark. Fox Talbot showed how a view of the Cloister at Lacock Abbey altered dramatically when the shadows became inky black, as a result of a different photographic processing. Brandt systematically increased the tonal contrasts in his pre-war prints when he returned to them at the end of his life, whilst Adams insisted that the print is to be regarded as analogous to a musical score, which can be transformed by interpretation of the tonal register and overall format. However, these two images by Palmer are individual, not variants of a single print. Their juxtaposition implies a lapse of time, perhaps of a few hours, perhaps of a longer period. After all, nothing is likely to be changing radically in that sparse landscape, invested with metallic waste. What, then, is the rationale of the near repetition? The element which I have not mentioned up to now is the pair of texts, written in HB pencil on photographic paper with letraset titling: DORPER SHEEP. These define for our benefit a particular kind of cross-breed 'between the Dorset Horn and the Black-Headed Persian' which is valued for its ability to 'raise its lambs on natural grazing in arid conditions'. The specifications for the breed define an ideal type for two particular derivatives of the breed: the Black-headed Dorper where black is predominantly 'confined to the neck and head', and the White Dorper, where 'pigmentation is acceptable around the eyes, under the tail, and on the udder and teats'. Note that what is being communicated here is not, in any strict sense a caption, let alone a personal description of the scene which we see before us. The text is clearly lifted from a reference source whose aim is to describe, without ambiguity, the special conditions governing the breeding of this type of grazing animal. Nevertheless, the simple juxtaposition of the images and the texts simulates a set of metonymic connections. In geographical terms, first of all, the provenance of the cross-breed, from its disparate origins in Persia and Dorset, leads us to think of the 'Western Cape' as a region onto which different patterns of settlement and agricultural exploitation have been grafted. 'Dorper', must after all (if it is not a corruption of the word 'Dorset') be a Dutch term imported by the Boer settlers. We can hardly doubt that the 'arid conditions' of the Western Cape are precisely those that are foregrounded in the two photographic images. There are cars, in these landscapes, and not the hardy sheep bred to resist the conditions of drought. But is not the accurate specification of the proportions and positioning of black and white on the two ideal types of Dorper sheep such as to make us think again about the change of light conditions which converts a darkened vehicle into a white one? That this work provokes such questions is beyond doubt. But it is equally clear that it does not put us in a position where we can claim to have answered them. In a particularly revealing interview with Pavel Bűchler, published in 1986. Palmer described the 'Dorper Sheep' as key piece because it 'opened up possibilities for exploring both metonymic and metaphoric associations in individual triptychs and also across the whole work'(2) In relation to that statement, we can surely say that Palmer's work has derived its characteristic momentum from privileging the metonymic over the metaphoric reading: that is to say, it has taken up a discursive form in which the chain of connotations is allowed to multiply, without giving the privilege to any one register of symbols. For a painter in the academic tradition, like Delacroix, Greece expiring on the ruins of Missolonghie is both the image of a beautiful Greek woman, in ethnic dress, gesturing amid the ruins of the destroyed city, and, at the same time, the symbol of a country fighting its war of national liberation. The image is perfectly expressive of the situation, and the political reading is irresistible. For Palmer, however, the prospect of desolation is not made emblematic in this way. It is, at least in part, a blank sheet upon which meaningful distinctions can be established; 'this is a Cortina, that is a Peugeot; this is a Dorper, that is a Persian'. Perhaps my favourite candidate for the book most resistant to translation is a hoary relic from the great age of French semiology: Pierre Guiraud's Sémiologie de la sexualité, published in 1978. Making it clear from the outset that it is not 'the physical reality of sex' that is at issue, but the process by which sex is signified in the operations of language, the work is a veritable feast of binary distinctions; ten classes of different registers of words used to denote the male member are noted, and no less than fifteen for the female, giving rise to an infinite possibility of further refinements and combinations. Between the simple binary distinctions of the code, and the poetic or demotic expressions in which sexuality find expression, there is a gulf, without a doubt. But Guiraud's treatise operates in the space between; it reveals the dynamic processes of the accumulation of meaning in a way that the highly emotive nature of the subject matter would lend to censor or obscure. In a real sense, Roger Palmer's procedure as an artist is a comparable one. Working in a context which is highly charged with political and ideological values, he selects his images not from the emotive register which photojournalism has made all too familiar. There is indeed hardly an image of a human presence in the whole course of his work. But there is throughout the whole course of his production a ceaseless concern to present the evidence of human presence, not merely in the form of the waste that a particular pattern of life has left behind, but also in the form of the human language that serves as the matrix for our interpretation of the visible world. It is this concern that has given his work an internal logic, as well as a exemplary form of reference to the past ten years. ------------ All of the work in this exhibition relates to Roger Palmer's engagement with South Africa. Having met his "coloured" South African partner in Britain, he made his first family visit to the Cape in 1985, at the high point of the Apartheid period, and began to work in two particular townships, one of which contained housing for the Cape coloured community and the other the abandoned village featured in Dorper Sheep. In 1989 he returned to the same area, and worked again in the abandoned village, which had been his wife's early home. This lay in a region 300 kilometres to the north of Cape Town, which had neither the favourable climate of the Stellenbosch area, nor the benefits of the Orange River valley, stretching further to the north. From the 1989 visit, there emerged in the first place a series of large upright photographic images (Untitled ), which is represented in part in the current exhibition. In each image, it is now a question of foregrounding the decaying outer walls of the surviving dwellings, and framing the vista of featureless land which stretches away towards the horizon. The houses were originally made with bricks derived from local materials. But unlike the reed houses traditionally built in the Orange River area, they represent a more forceful intrusion into the environment. It will be a process of decades, rather than years, which sees them revert once again to the condition of the earth from which they were made. Meanwhile the unassimilated detritus of the human habitation - metal parts which are rusting and blackening - continues to clog the place up. The abandoned vehicle is probably not far away. Palmer does not need to inflect this set of images with a further group of texts. The system is, in a sense, already in place. The 'precious' quality of the photographic materials forms an all the more vibrant alliance, in these large-format works, with the accidental and abraded surfaces of the dilapidated buildings and their desolate setting. Yet this visit was to be followed in 1991 by a further use of the text as marker, which struck up a reciprocal relationship between the deserted family home and his own newly established house in Cape Town. On this occasion, he discovered in his wife's previous home a cache of newspapers and other forgotten materials. These became the basis for an environmental work at once personal in its associations and impersonal in its approach. The masthead of the Cape Argus, dated 23 March 1966, was reproduced on a photocopier and then transcribed in a pencilled version (which did not omit the slight distortions of the letter forms produced in the process of copying) on to the interior walls of the house. Such a reference both to the previous history of South Africa, and to the childhood years of his wife, inevitably recalls the problematic blend between public and private reference which we find, from our own perspective, in the early Cubist collages of Picasso and Braque. Indeed one of the strategies of the thought-provoking High and Low exhibition held recently at the Museum of Modem Art, New York, was precisely the revival, through copious documentation, of the full visual context of the fragmentary mastheads and headlines which the Cubists artists had torn from their newspapers. What can such a restitution of context teach us? In a real sense, Palmer's very different strategy has answered that question. The fragment can never restore the plenitude of the past situation, historical or personal. But it remains an index of a relation between past and present; in this case also, between a previous home and a present one. It is a translation from one time to another, and from one space into another space. That Palmer was also attentive to developing his own personal thematic, exemplified in the light/dark contrasts of the photographic image, is also apparent when we consider the other scheme which he installed in the village to the town house. The location of the Cape Town house was in the Observatory residential district. Here he installed a sequence of texts taken from the astronomical pages of a 'Victory Atlas' published around 1919 by the Daily Telegraph and bought in Newcastle upon Tyne about twenty-five years before. The Atlas incorporated astronomical charts, with Greek lettering and a Roman translation, as the key to a map of the night sky. These symbols were classed according to the level of brightness. The inscription on the white wall therefore alludes at the same time to the scale of light and dark, the condition of visibility and therefore of intelligibility in the human world. The visit of 1991 was a preclude to a longer period spent living in Cape Town, which ended in 1993. Over these three years, he not only continued to produce photographs in series, comparable to the ones already discussed, but also developed panel paintings and environmental drawings relating to the projects at his own home. From now on, the photographs (as in the previous Untitled groups of 1989) were without additional written captions. But they were invariably invested with a dense signification, which was underlined and given an ironic dimension by the use of the title. For example, the series Discovering South African Rock Art (1991) bears a title adapted from a scholarly book on the rock paintings of the area which are among the earliest surviving examples of art in Africa. The location of Palmer's four photographs, how ever, is the dockside at Cape Town, where the massive stone wall bears a series of painted inscriptions bearing reference numbers and indications of the weight of each block in kilograms. The appearance of such data in the context of a contemporary art exhibition inevitably brings to mind the use of self-referencing systems in the conceptual displays of an artist like Lawrence Weiner. But the oddly delicate stencil of the running springbok lends particularity and a sense of place to the repeated images. Palmer has also used the features of the Cape Town docks in his other series Line of Defence, where only the inscribed dates differentiate the summits of the hollow concrete pyramids placed as a defence against the sea. In this case, the connotations are more directly political in their allusion. The dates refer to a history in which South Africa did indeed exhibit lines of differentiation; in which the country's defence took the form of cruel demarcations within a single species, and the coding of such differences according to the vocabulary of colour. Recent exhibitions of paintings, sculpture and photographs relating to the Holocaust have underlined the particular aptitude of the photographic series to assume the burden of the unsayable. Painting and sculpture have their own traditional way of expressing the suffering of humanity, and it is virtually impossible for an artist working in these media to escape from these traditions. Thus the artist becomes part of a lineage of other artists, and the message is assimilated to the great narratives of suffering and redemption which dominate Western culture. Photography, by contrast, contrives to escape from this legacy. The photographic series, in particular, seems to fulfil the ambition nurtured by Theodor Adorno that avant-garde art should represent the dehumanisation of modern society by espousing its repetitive structures. To quote from his essay on Stefan George: 'What survives is determinate negation'.(3) This message seems to me to be reinforced by the particular expressive charge which Roger Palmer's photographs develop when they have least to say, in the way of reportage or journalistic commentary on South African society. The group entitled Blanc de Noir takes its title from the sophisticated nomenclature of oenology: a white wine is produced from black grapes by passing the must rapidly over the skins. The images to which the title refers, however, display successive stones used as markers to point the way to a gate: each is white as a result of the successive coats of whitewash which have been used to increase its visibility, but casts, in the strong sunlight, an inky black shadow. The set of four photographs under the title Chain of Signs reproduces a series of hand-painted signs directed at train-drivers. Outside the specialised code to which they refer, these signs have no operational significance. To us, they are so many blank surfaces, displaying a range of tonal possibilities and the vestiges of a changing landscape. In works like this, Palmer's particular aesthetic end seems to be to attain what Roland Barthes would call the 'degre zero': the neutral, uninflected display of a code which has no rhetoric attached to it. It is in the nature of communication, however, that such a code can never be attained; and to achieve a near miss is to release unexpected possibilities of creative interpretation. Roger Palmer's photographic work in South Africa over the past few years seems finally to be summed up in two single images. These stand alone, precisely because they derive their iconic quality from an internalised contrast, or contradiction. KEEP OUT DANGER frames a massive and mainly unpolished surface of rock, on which a crude message has been painted (evidently with a spray-gun). The message, read from left to right, seems to crumble visibly into the texture of the undressed stone. White over Black represents at once the most open and the most over determined of messages, profiled against a semi-industrialised landscape. The shadow (undifferentiated black) repeats in miniature the flag-like form of the sign. Further commentary would seem superfluous. ------------ This essay began with the suggestion that Roger Palmer's work is an allegory of the process from which it derives its material form. This inevitably led to a discussion of that process in the sense of the photographic medium which he has used consistently throughout his career. Tracing the sequence of recent photographic works, as I have now done, is a way of emphasising to what degree he plays upon the technical presuppositions of the medium. In particular, the special tension which results from the encounter between the 'common' materials of everyday bricolage and the 'precious' materials of fine photography is a resource to be drawn upon, and given supplementary significance. Yet in view of the highly coded nature of these communications, we could assert that everything in Palmer's work - every image offering a brief glimpse of a specific terrain is put forward as a form of linguistic demonstration. Black and white photography depends on the specific difference between light and dark registration. All its most delicate nuances (a distant telegraph pole, a piece of metal detritus) arc dependent on a specific modulation of the intermediate tonal range. This is true of all black and white photographs. But in very few is the anti-mimetic drive strong enough to make us aware of the fact. Language is also, however, interpersonal communication. When we talk of the 'language' of an art form, we elide for the moment the point that signs are not autonomous and self-referencing, but tokens of exchange, and indeed forms of action. Palmer's recognition of this fact has led to a specific series of new developments in his art over the past few years, to which the current exhibition bears witness. Most important, no doubt, was his decision to include work by the South African artist already mentioned, Chickenman Mkize, in the exhibition which he put on at Cape Town in 1992. Mkize had originally worked in a dairy and been pensioned off. His account of the way in which he came to produce his sculptural objects, involving signs reminiscent of his former employment, is interesting: in his words, he dreamed of the objects, and was told that he had to bring them into being. They are, however, signs on a secondary level: drawings which reproduce the characteristics of writing rather than operational instructions. Palmer's inclusion of a large selection of these pieces next to his own was not, in any sense, the annexation of a 'primitive' dimension to complement his own discourse (as the Surrealists were wont to do with 'naive' artists like the Facteur Cheval). It was an attempt at a mise-en-scéne which was also a form of translation: Mkize's own second-order discourse on the repertoire of found signs was aesthetically analogous to that of Palmer himself. Homi Bhabha has recently written a fascinating article under the title: 'Beyond the Pale: Art in the Age of Multicultural Translation'.(4) His theme is specifically the artists of non-European, and particularly Asian origin who now work within the artistic communities of the Western world. Yet the Pale is traversable in both directions. Roger Palmer's word pieces, shown in the 1992 exhibition and at the pr e sent one, are indeed meditations on the process of multicultural translation which take their multi-lingual texts from simple glossaries of commonly used terms in the chief South African languages of Tswana, Xhosa, Afrikaans and English. Colour vocabulary is one of the repertoires used, and the references set up the same type of analogical and differentiated relations of figure and ground as we have seen already in the case of several of the photographs. These works, whether drawn on the wall or painted on canvas, are no less concrete in terms of their particular technique than the framed photographs. And, just as relations of light and shadow create a supplementary message in the case of the photographic images, so the phenomenological complexity of colour produces a perceptual effect which is a unique occasion of vision. Grey lettering reads differently on a white and a black background. Light grey on white looks the same as dark grey on black. Here again the code requires that such terms should be differentiated. But the relativity which reveals the instability of such differences is unavoidably brought home to our experience. In the end it hardly has to be said that these varied media and disparate techniques bear the mark of one artist. Or to put it more precisely, they testify to a particular sensibility. The remarkable thing is that Roger Palmer has risked a great deal in his long-standing engagement with another culture, but that the very need to find alternative modes of signification has reinforced the consistency of his programme. Sensibility is not dissociated in these variations of medium and technique. Sense is preserved through the very testing of its limits.

1. Nicéphore Niepce, Correspondances 1 K 25-1829 (Rouen: Pavilion de la Photographic, 1974), p.145. 2. Roger Palmer - Precious Metals, Serpentine Gallery, 1986, unpaginated interview. 3. Theodor W. Adomo, Prisms, translated by Samuel and Sherry Weber (London: Neville Spearman, 1967), p.226. 4. See Homi Bhabha, 'Beyond the Pale: Art in the Age of Multicultural Translation', Kunst & Museum journaal, Vol.V, No.4, 1994. |

|